Time to Nationalize the Amazon and ‘Amazonize’ the World

Caetano Scannavino, coordinator of the NGO Projeto Saúde & Alegria, operating in the Amazon for over 30 years, and member of the coordination of the Climate Observatory. This text was originally written for issue 88 of the WBO Newsletter, published on October 13, 2023. Fill in the form at the bottom of the text to access and subscribe to the WBO weekly newsletter in English.

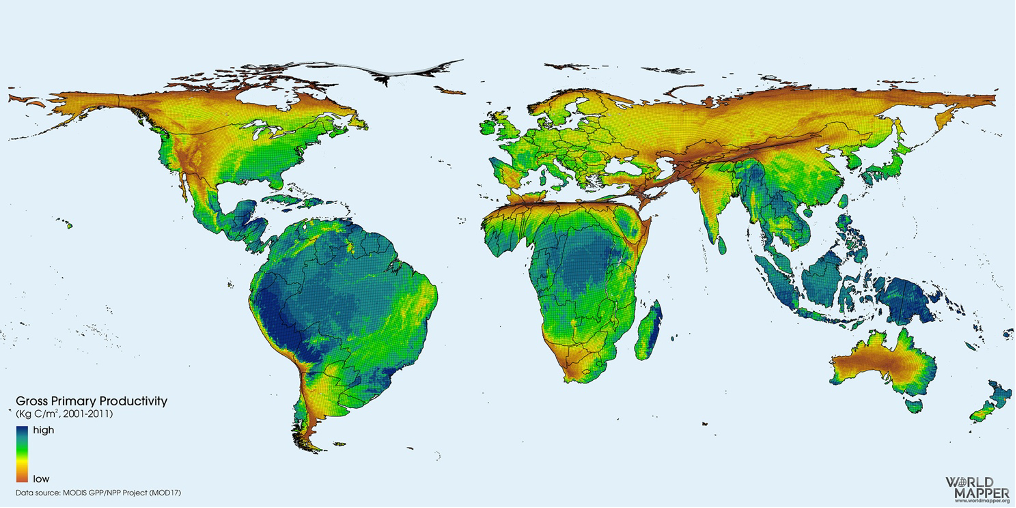

If life is the greatest wealth that exists, Brazil is the richest country in the world, according to Gross Primary Productivity, which measures the synthesis of organic matter generated from water, light and air.

The Amazon is a factory of life that, just with the protection of Brazilian Indigenous lands as a measure to combat climate change, could yield US$523 billion to US$1.165 trillion in 20 years with the global benefits of carbon and ecosystem conservation (Climate Benefits, Tenure Costs).

It's sad that our Indigenous and traditional peoples, while providing voluntary service as guardians of the natural assets that keep us alive, receive in exchange bullets, mercury and diseases from the outside world instead of health, education, sanitation, energy policies, among other measures to ensure their well-being. Without social justice, there is no environmental justice.

We have already devastated an area equal to two German Amazon regions, in which 63 percent of the land is now occupied by extremely low-productivity pastures and another 23 percent has been abandoned, according to data from Inpe and Embrapa. We deforest to become poorer. IPS Amazônia data identifies the worst Social Progress Indexes precisely in the municipalities that deforested the most.

It is difficult to talk about sustainable development without first resolving the culture of illegal acts that prevails in the region, where the illegal is legal. We allow a few to appropriate wealth—gold, wood, land--that belongs to all Brazilians. They don't pay taxes and still leave a bill for the damage. Those who want to do the right thing cannot compete with the low price of illegal extraction, so they fail or change sides. Instead of responsible investments, cartels and criminal organizations end up being attracted to the region.

LIFE MAP – If life is the greatest wealth, Brazil is the richest country in the world according to the GPP map, cumulative production (synthesis of organic matter) generated by water, light and air. “The ability to generate life”, according to Julia Sekula, co-author of “Brazil: Restaurable Paradise”.

People kill and deforest in a collusion between private and public actors. In Brazil, which is among the three most dangerous countries in the world for environmental defenders, the fact that, of the 300 murders of activists in the Brazilian Amazon, only 14 went to trial in the last decade cannot be normalized (Human Rights Watch, 2019).

After a government that scrapped monitoring, inspection, and punishment mechanisms, rebuilding command and control policies and strategies is a first step. Protecting the Amazon, before being a foreign issue, is a national interest. Without the biome, the average temperature would rise 0.25 ºC on the planet, but it would jump 2 ºC in Brazil, where 25 percent of rainfall would also be lost, making agriculture and energy generation unfeasible, according to Tasso Azevedo, coordinator of SEEG (Greenhouse Gas Emission Estimation System).

Demanding support from rich countries is more than asking for a favor. It is a right. After all, the benefits generated by the Amazon are global and conservation costs remain local. To do this, you must have an agreed-upon project for the region. Sovereignty is offering paths that combine social and environmental solutions, which are fairer and more justly compensated.

One of them is to shield the forests and focus on increasing efficiency in consolidated agricultural areas, producing more with less land, and without deforestation. Ordering large-scale agriculture in the region is a damage reduction strategy, especially because cattle and soy are far from being Amazonian vocations.

By the way, starting at US$20 per ton of carbon, it is more profitable to restore the forest than to raise cattle in the Amazon. If livestock farming were replaced by regeneration, the country would be able to capture 16 gigatons of carbon from the atmosphere and would receive around US$320 billion in 30 years ("Carbon and the Fate of the Amazon").

A robust restoration and socio-bioeconomy policy can, after decades, finally make Amazonia take off from the meager 8 to 9 percent share of the national GDP. “Brazil’s great potential is biodiversity”, says scientist Carlos Nobre. “Agroforestry systems with açaí can yield up to US$1500 per hectare annually, while livestock earns around US$100/hectare.”

The participation of the Brazilian Amazon in the global market for products compatible with the forest, such as nuts, fruits, peppers and others, is negligible. Despite representing 30 percent of the world's tropical forests, it occupies only 0.18 percent (US$300 million per year) of a market worth almost US$200 billion (“Opportunities for the Brazilian Amazon”).

In the Amazon alone, science has been discovering a new species every two days in recent years (New Species Report - WWF/Mamirauá). It makes perfect sense when they say that deforesting a primary forest is like deleting a hard drive without knowing what's inside, including possible discoveries of treatments for diseases that have not yet been cured.

If we lack resources to invest in research and technology, partnerships are welcome, as long as they are through fair cooperation mechanisms, respect for the rights and knowledge of Indigenous and traditional peoples, in order to protect and adequately manage all these assets and knowledge in the service of humanity.

“Brazil has everything it takes to lead a movement from the Global South for fairer global climate governance. We have two years to decide the fate of the rest of the century”

Caetano Scannavino, coordinator of the NGO Projeto Saúde & Alegria, operating in the Amazon for over 30 years, and member of the coordination of the Climate Observatory

Universities in the region have trained people to leave. In an Amazon region that is more than 70 percent urban, it would not be prohibitive to envisage strategic hubs with low-carbon technological plants, which train the local workforce with a focus on innovation, processing, and adding value to socio-biodiversity inputs. If the fiscal benefits of the Manaus Free Trade Zone are to be valued, why not make it, for example, a Silicon Valley of the Standing Forest, a global center for the bioeconomy and biodiversity?

In times where riches begin to change color, from the black of oil to the green of the standing forest, our decision makers should turn to legislative proposals that look towards the future, instead of wanting to perpetuate an outdated model that has gone wrong, insisting on bills to release cattle into Extractive Reserves, mines on Indigenous lands, and the maintenance of loyalty to the culture of crime that pays off by rewarding land grabbers with discounts of up to 98 percent for the acquisition of stolen public lands.

For these solutions to happen and gain scale, much more than international pressure is required. Brazilian society needs to take responsibility for compliance with the laws, for the socio-environmental measures that are not about the right or the left, but are effective state policies that consolidate a new culture in which good practices predominate.

If we do our homework, from Amazonia, we will have all the conditions to reverse the order, guiding instead of continuing to be guided. Brazil has everything it takes to lead a movement from the Global South for fairer global climate governance. We have two years to decide the fate of the rest of the century. The opportunity is there with Brazil assuming the presidency of the G20 in 2024, and of COP30 in 2025. This is important because the ten-year review of the Paris Agreement will be held in Belém. Then we will know if we want to reach 2030 discussing an increase in temperature of 1 to 2ºC or 2 to 3ºC.

As a colleague in this struggle rightly says, instead of internationalizing, the time is to “nationalize the Amazon and Amazonize the world.”